The Prisoner’s Dilemma Of Chinese Education: Examining Educational Involution in China

Category: Contemporary, Tags: China, Education, Essay

Introduction

It is well documented that Chinese underage students experience enormous stress from academic competition. A survey from Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Report on National Mental Health Development in China (2019-2020) using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale or CES-D showed that 17.2% and 7.4% of Chinese teenagers had mild and major depression (Hou & Chen, 2021). Another survey from I research (Airui Zixun) (2019) showed the average daily sleeping time of Chinese middle school students is 6.82 hours and 59.4% of them sleep less than 7 hours everyday. Data from National Health Commision of the People’s Republic of China shows that in 2018, 53.6% of Chinese teenagers and 81% of Chinese high schoolers have myopia (Chinanews, 2020). A question that naturally arises is: what are the fundamental causes of academic competition and stress in China? If we answer that question successfully, we can then discuss the nature, necessity, and avoidability of the competition and stress. In this essay, I will first briefly introduce the relevant existing literature on Chinese education. Then, I will explain my methodology and angles. After that, I will present my hypothesis and evidence. Later on, I will provide my suggestions to the current Chinese education system and close the essay.

Existing Literature

There is plenty of research on Chinese education and students. Many focus on the historical development and current characteristics of the Chinese education system and compare it to foreign systems. I will categorize these researches into a few common explanations for the intensity of competition and stress in Chinese compulsory education.

Culture and History

China has a long history of distributing social and political positions through national examination. The civil service examination (keju), embedded in Confucianism, dates back to the Sui Dynasty 1400 years ago and persisted until late Qing (Wang, 2019). Compared to the West, the legacies of Confucianism and Keju lead to a national emphasis on studying and examination, which can be witnessed in East Asian countries like Korea, China, Japan, Vietnam, and Singapore (Xiong, 2021). Although such an exam-oriented attitude was criticized during the cultural revolution, it soon returned to mainstream thinking after economic take off during the reform and opening-up (Howlett, 2021). Therefore, it seems less strange when practical and agnostic Chinese students and parents attend worship at Confucius temples for higher scores (Howlett, 2021).

Overpopulation and Underdevelopment

Another explanation is also well-accepted by the Chinese public: China is overpopulated and underdeveloped, so intense education and competition is necessary due to scarcity of resources (Howlett, 2021). This argument is straightforward. China as a middle income country with labour-intensive industries lacks prosperous domestic demand and high-value-added professions. The average workers in agricultural, industrial, and service sectors have been poor and only the highly educated professionals are entitled to the primary distribution of gains from economic growth.

Social Stratification and High Mobility

Compared to the communist China and Western social democracies, modern China is highly unequal. Inequality itself does not necessarily entail intense competition. When mobility is low, such as under feudalism, people do not stress about competition because there is no chance for upward or downward mobility. But China is currently characterized by high inequality and high mobility (Whyte, 2012), which means there is both a high chance and high expected return from better education and employment. Therefore, although absolute wealth is growing spectacularly, it seems harder for the middle class to maintain their hierarchical social position (Liu, 2020). Almost inevitably, parents transfer their “class anxiety” to their children.

One-Child Policy and Population Ageing

When each family has only one child, the whole family’s hope of upward mobility and financial security (Zhao, et al, 2015), especially given that the Chinese population is ageing and old-age-dependency ratio rises rapidly (Han & Cheng, 2020). When one child is expected to earn the surplus of two or three children, they are required to be academically competitive and successful.

Gaokao and Exam-oriented Education

Gaokao and the whole exam-oriented education system often come under attack. Many argue that the system focuses on teacher-centered cramming and memorizing while students cannot develop personal interests and enjoyment during the studying (Zhao, et al, 2015). Some suggest that the Chinese education system needs to diversify and emphasize critical thinking and universities should admit students using their own criterion rather than the one-size-fits-all gaokao (Kang, 2004).

Unequal Distribution of Education Resources

The 46th article of the Chinese Constitution requires that “the citizens of People’s Republic of China are entitled and obligated to receive education” (Xianfa, 1982). The 4th article of the Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China assert that “all school-age children and teenagers with the citizenship of the People’s Republic of China, regardless of genders, ethnicities, races, family financial conditions, religious beliefs, are entitled to equally receive compulsory education in accordance with the law and fulfil the obligation of receiving compulsory education” (Yiwu Jiaoyu Fa, 1986). However, in effect, educational resources are unevenly distributed. Besides the urban-rural divides based on Hukou and the regional divides, the inter-school divides within the same regions due to the school district houses (Xuequfang) system where parents buy expensive houses as entrance ticket to prestigious schools further embodies the economic and educational inequalities in China (Tang, 2018). In addition, universities have different quotas for provinces and it is well-known that Beijing students are much easier to enter the top Chinese universities located in Beijing (Howlett, 2021). Moreover, the privatization of education in the form of expanding private tutoring also adds to the inequality. A study finds that, not only the rich have more access to private tutoring, single children, non-boarding students, non-left-behind children, healthy children, children from wealthy families exhibit higher increases in scores from private education (Xu, 2020).

Failure of Education Reform

Many scholars, researching extensively on government documents and announcements, pointed to the decades-long effort from the central government to reform education and reduce burden (Jianfu) and argue that the central government has long acknowledged the extent and harms of over-competition in Chinese education. They drew on surveys and historical cases and faulted the local schools, governments, and parents for not fulfilling the central government’s education policies (Zhao, et al, 2015; Dello-Iacovo, 2009; Chen, 2021).

Educational Signaling

The market signaling theory is a relatively new model that explains society’s pursuit of higher education levels (Benjamin, et al, 2017). The model sees education as a filter, signal, or sorting device; it does not enhance workers’ actual productivity, but employers with imperfect information favour academic high achievers because they believe that academic high achievers happen to be innately more hardworking and productive (Benjamin, et al, 2017). In the Chinese context, He Zun (2012) used the signaling theory to analyze credentialism in China. In the midst of short-term oversupply and high unemployment rates of college graduates due to the expansion of public colleges in the 1990s, He (2012) argued that the society at large still unwittingly believes higher education (not including vocational training and work experiences) means better abilities and jobs even though the reality showed otherwise.

Methodology

I believe that all of the arguments above are true and have their merits. However, one perspective borne out of the interaction of all these factors deserves more attention, which is the concept of involution. In the next section, I intend to use a thematic analysis on the recently popularized notion of involution on Chinese internet. I will first explain the concept and hypothesis of involution in the context of Chinese education. Then, I will present relevant data to examine the implications of education. However, macroeconomic data themselves can hardly prove causations, so I will reply on two detailed case studies of the two most contentious education topics (besides the suicide incident at 49th High School of Chengdu) on Chinese internet this year: Hengshui High School and the 7-year-old girl Niuniu. These two cases blew up on the internet because they are relevant to almost every student and their parents in China. A deeper examination of them allows us to visualize, contextualize, and critically assess educational involution in China. Through this process, I can observe and interpret causations and test the involution hypothesis by comparing the assumptions to reality. In addition, I will employ game theory, structural functionalism, and social conflict theory in deriving intentions and causations. I will also further explain my methodologies in the next section.

Evidence/Findings

History and Hypothesis of Involution

In Chen Guohua (2014)’s “On the Involution of Governance of Compulsory Education in Minority Areas,” he explained the origin and evolution of the term involution. Involution was first used by Immanuet Kant, who contrasted it with evolution. American anthropologist Alexander Goldenweiser, the first who applied the term academically, used involution to describe a cultural stage where when outward expansion is strictly restricted, the culture can neither stablize nor evolve into a new form, but to involute by increasing the internal complexity and inefficiency. He later referred to Indonesian agriculture after World War II as an example of involution, as it was characterized by overpopulation, limited agricultural land and technology, and subsequently inefficient agriculture. Afterwards, Huang Zongzhi also used involution to describe some agricultural economics in Yangtze Delta where the total agricultural output expanded at the expense of decreasing marginal returns. Ruth Jonathan (1990) used involution to describe the disruption of private schooling to American education, although her focuses and arguments are not identical to mine in this essay. Gradually, the use of involution popularized in describing cultures, institutions, governments, social welfare systems, and eventually exploded on Chinese social media amidst the discontent towards 996 working schedule and stressful high school studying.

Although not every netizen using the term educational involution shares an identical, precise, and academic definition, its meaning gradually stabilized. Educational involution is a form of prisoner’s dilemma, where the Nash equilibrium best response for each individual student (and their parents) is to study harder and longer, while students as a whole become worse off. Therefore, individual students rationally achieve an overall irrational outcome.

Specifically, the process of educational involution includes the following steps:

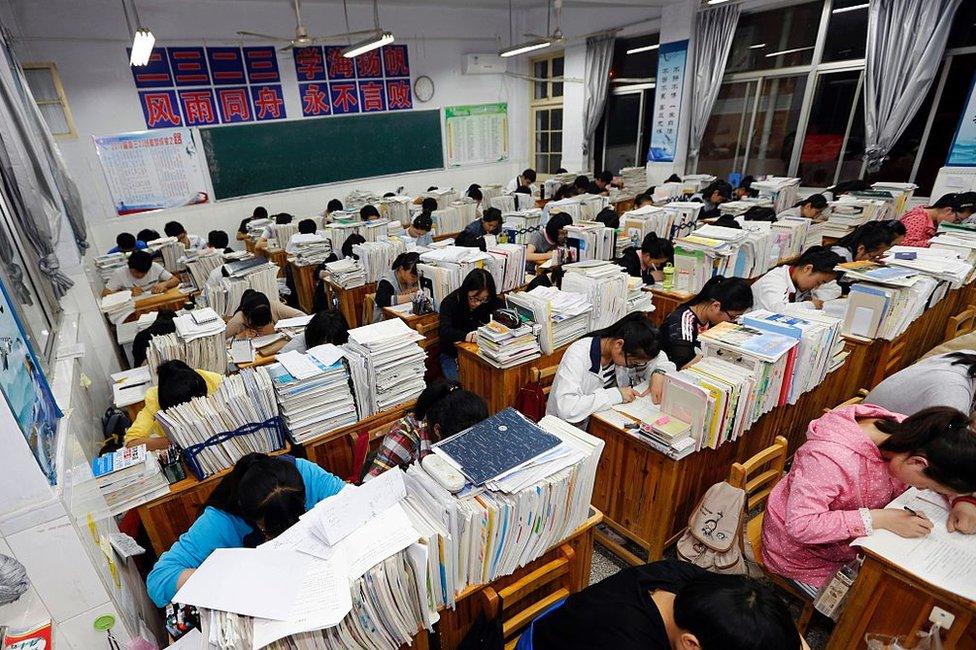

- As Chinese middle class and white collar families expand, students under high expectation study harder and longer, attend private tutoring schools, and learn more complicated and detailed information at the expense of their health and family financial security in order to gain higher scores and a relatively higher position.

- Meanwhile, since the efficiency in Chinese compulsory education has improved due to the effective execution of compulsory education and improvement of teacher qualities alongside the growth of private tutoring industry, students gradually approximate or even break through what they (and previous generations) are expected and required to learn in the stage of compulsory education. In other words, they successfully complete the curriculum requirements.

- Witnessing an uptick in students’ exam scores, the public educational systems, due to the short-term lack of high-quality advanced education resources such as the capacities of top universities, have to respond with raising the difficulties of exams including gaokao and set up higher bars for all students.

- Given (2) and (3), teachers and professionals from the Ministry of Education have to expand the curriculum or include beyond-curriculum (Chaogangti) questions in exams. However, these added questions and requirements are above the original standard set for the 9 years of compulsory education plus 3 years of senior high school, many of which are not useful or mandatory from a practical point of view. Students either will not apply them in later lives, or can totally learn them later if reality requires. Therefore, these added contents are barely anything but a filter whose only purpose is to make students work harder on meaningless topics to acquire the same educational resources and positions.

- Because exams become harder due to (3) and (4), students are more pressured to study longer and attend private tutoring. The situation goes back to (1), starting the next identical loop.

This positive feedback loop and vicious circle induced by a structure of prisoner’s dilemma is roughly explained by Yang Zhenfeng, the principle of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission:

When a portion of students get tutoring, their scores will increase. However, when all students get tutoring, what will increase is perhaps only the cut-off scores for university admissions. The result of the theatre effect can only be that students sacrificing their time for all-round development to repeatedly practice and practice repetition, repeatedly train and train repetition. It not only harms the students and affects their comprehensive growth, but also brings unnecessary financial burden to the family. (Xinmin Wanbao, 2021)

Note that in a loop from (1) to (4), it is much easier to prove (1) and (3) than to prove (2) and (4). Due to the space constraints in this essay and my limited abilities, I will focus more on the examination of (1) and (3) using observable data and case studies. Therefore, in the following subsections, I will first briefly examine (4) by discussing curriculums. Then I will introduce quantified macro-level data and see if the data fits (1) and (3)’s predictions. Afterwards, I will move to the intermediate level of provinces and schools to examine (1) and (3)’s presence. Finally, I will move to the micro-level of a specific student and her family to verify (1) and (3)’s correctness in an individual case.

The Curriculums and Rules

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence of the “uselessness” of school content from compulsory education to university education, especially after 2000 when high-skilled technicians are needed more than the average college graduates are (Jingji Cankao Bao, 2017). For example, many doubt that 18-year-old students or the average citizen needs calculus, level 5 English in their daily lives, or the geography of Peru in their daily lives. Certainly, some of these comments have anti-intellectual tendencies and by themselves are not rigid enough for academic discussions. Therefore, we move to one specific rule that is worth discussing, which is the prohibition of the beyond-curriculum (Chaogang) techniques in math gaokao. From my personal experience, beyond-curriculum questions, techniques, and solutions had been common in math exams. They are beyond-curriculum because teachers do not, or are not required to, teach these categories of concepts in classrooms, but they do appear, or can be advantageously used, in exams. The subtext here is students are required to go to private tutoring for additional but semi-necessary help or/and devolve a large portion of their time to figuring it out by themselves or with classmates. By doing this, teachers and schools can bypass the “burden reduction” (Jianfu) rules. In extreme cases, public teachers intentionally leave out lecture contents and tell students to attend their private tutoring—which is illegal because Chinese public teachers are prohibited from holding paid private tutoring—to learn about beyond-curriculum exam questions (Xiaoxiang Chenbao, 2020).

To address the problem of beyond-curriculum exam questions, some high schools and gaokao explicitly prohibit the use of certain math methods such as L’Hôpital’s rule and Lagrange multiplier, arguing that allowing advanced techniques will put other students who successfully and only fulfil curriculums’ requirement at disadvantages (Zhang, 2018). But not everyone agrees with this approach. Zhang Jinsheng (2018), a high school teacher from Jiangxi, even published a paper titled “I Give Beyond-Curriculum Questions When I Create Exams, You Use Beyond-Curriculum Solutions When You are Smart” (Wo Ming Wo Chao Gang, Ni Yong Ni Gao Ming). Media professional Ma Dugong (2021) also criticized: “why force students to use troublesome and lengthy methods when there are superior and quicker methods?” The latter referred to beyond-curriculum techniques.

With these observations, one cannot readily prove (4) correct or incorrect, but it does show a conflict between recognizing the advantages of the high-capacity students and maintaining an equalizing policy in accordance with the curriculum.

Macro-level: Quantitative Data

From the hypothesis, (1) would predict an increase in students’ learning abilities, studying time, and private tuition cost as time goes, while (2) would predict an increase in the difficulty of exams.

OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (2015; 2018) examined average Chinese students from Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Guangzhou in 2015 and from Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejinag in 2018. Chinese students, although not the same groups of students, exhibited remarkable improvement in a short 3-year period, even though they had already been the top students worldwide. The overall reading, overall mathematics, and overall science scores went from 494, 531, 518 to 555, 591, 590. In addition, Macau’s scores had also increased considerably. Programme for International Student Assessment. (2015). Another study published in Nature Human Behaviour compared the STEM skills of university students from China, India, Russia, and America found that Chinese students had highest levels of critical thinking and academic skills at the early stages of university, but they uniquely experienced “substantial…. absolute losses in academic skills” in later university studying (Loyalka, et al, 2021). One possible explanation is that Chinese students are in control of an uncommonly high level of academic skills at the time of gaokao but quickly forget them in universities either because they are not useful anymore or they are just too much to remember chronically. Some internal Chinese data can also prove the trends of higher education capacities. Data from the Ministry of Education (2020) showed that the consolidation rate of compulsory education went from 93% in 2015 to 94.8% in 2019. In the same period, the 3-year-before-compulsory-education kindergarten enrollment rate increased from 75% to 83.4% and high school enrollment rate grew from 87% to 91.2%. Moreover, dropouts during compulsory education reduced from 600 thousand in the beginning of collecting this data to 831. On the other hand, the market size of k12 (from kindergarten to grade 12) outside-of-school tutoring grew from 293.3 billion yuan in 2013 to 768.9 billion yuan in 2019 (Chanye Xinxi Wang, 2019), confirming the prediction of the growing tutoring industry.

As for the prediction of increasing exam difficulty, Du (2020)’s “Research on the change of the content of science mathematics test paper in the new curriculum standard of college entrance examination in recent ten years” employed sophisticated quantifying methods and concluded that there is no changes in difficulty of science and math gaokao. However, if one goes to the websites of top universities, one can see that the admission scores rose steadily. For example, the cut-off scores for Peking University increased from roughly 640 in 2011 to 680 in 2021 for Beijing students (I said roughly because there are variations based on exam paper types) (2021). Therefore, these statistics align with and do not falsify the educational involution hypothesis.

Intermediate-level: Case Study of HengShui High School

Quarrels about Hengshui High School erupted after Zhang Xifeng, a student from Hengshui High School, gave a motivational speech on a TV program in June, 2021. The speech went viral not only due to its highly agitating and theatrical effects, but also due to its offensive and provocative tone packaged in the name of motivation. In the speech, Zhang, playing on a Chinese idiom, referred to himself as “a rural pig who wants to dig the cabriage in the city” (Xinhua Baoye Wang, 2021). He repeatedly labeled himself as “an ordinary (Pingfan) person,” but despised “mediocre (Pingyong) people” who earn “2000-3000 yuan per month” (Ke, 2021). Many did not buy his distinction between “ordinary” and “mediocre,” they thought he had gone too far on the motivational attitude that he saw himself above everyone else due to his higher scores and perceivably better jobs.

However, Hengshui High School has not been an elite school, at least not in the conventional sense. Li and Luo (2021)’s “The Underlying Logic and Institutional Governance of Super Secondary Schools: A Reflection and Review Based on the Hengshui Model,” they traced the history of Hengshui High School. Its founding dated back to 1951, but as a poor school in the poor city Hengshui in the poor province Hebei, it was simply another rural high school. Things changed when, in 1993, principal Li Jinchi “closed the school gate” and turned the school into a closed and paramilitary full boarding school (Sohu, 2019). The schedules are specified to each minute, students are required to wake up at 5:40 am to morning jog, go to bed at 9:58 pm, and are not allowed to go to the washroom between 9:58pm and 11:30pm (Sohu, 2019). Students are reprimanded for sitting on the bed at times supposed to sleep, going to the washroom at incorrect times, sleeping naked, studying after 10pm (Sohu, 2019), and interacting intimately with classmates of the opposite sex, which is termed “innormal contact” (Zhang, 2018). Meanwhile, Li Jinchi also spent large sums of money, some of which was paid by the government, to recruit best teachers in the provinces (Zhang, 2018).

The school quickly achieved an extraordinary victory. In 2002, the university admission rate rose to 92%; in 2015, 88.6% of the students were admitted by tier one (yiben) universities, the highest in the province; in 2019, 275 students were admitted by Peking University and Tsinghua University, accounted for 90% of Hebei’s quota (Zhang, 2018). Hengshui High School, originally a public school, quickly capitalized, expanded, duplicated its success, and profited from its brand. In 2013, Hengshui High School partnered with a real estate company to found the private Hengshui No.1 High School (Li & Luo, 2021). Until 2021, 19 “Hengshui” High School across China were established by Hengshui High School’s partner Yunnan Changshui Education Holding Company, which went on New York Stock Exchange in the name of First High-School Education Group Co., Ltd (Li & Luo, 2021).

Hengshui High School’s success is not complex. It operates as a total institution that squishes students into gaokao machines. It seems like a win-win situation for both students and the school. However, many other high schools are trying to duplicate its simple success as well. Perhaps the most notable example is Lijiang Huaping Women’s Senior High School in Yunnan, whose principal Zhang Guimei was popularized due to her effort of sending 1804 girls out of the poor mountains through gaokao (Yi, 2021). However, she required all girls to keep their hair short, sleep 5 hours per day, and finish each meal in 10 minutes (Yi, 2021). Rethinking its “success,” does “Hengshuization” or “Hengshui Style” represent a bright future of Chinese education? It is not hard to see that if every school maximizes their admission numbers by pursuing the Hengshui model, the results will be disastrous for society overall.

Micro-level: Case Study of Niuniu

For Niuniu’s case, I will rely exclusively on Southern Weekly’s “Prestigious Teacher, Nit-Picker, Mole, and the Parents’ Commision” (Mingshi, Citou, Neigui, He Jiaweihui) on November 26 (Qian & Zhang, 2021) because it is by far the most authoritative and detailed report. Niuniu was a 7-year-old student in an elementary school in Guiyang. One day, her parents complained to her teacher that he assigned too much homework that they had to help Niuniu finish her homework. The teacher, who is well-renowned in Guiyang, was not willing to make changes even though other parents also complained that “their child had to wake up early to do homework”, “the Chinese homework was too much and beyond-curriculum,” and “their child vomit before exams.” After Niuniu was ordered by the teacher to stay in his office to make up her homework that she did not finish due to a hospital visit about her allergic cough, her allergic cough developed into acute asthma and she had difficulty breathing. Her parents were extremely upset, they went to the principal and it seemed they eventually reached consensus with the teacher. What they did not know was that the second day following the asthma incident, other 37 parents in the parents’ commision created a petition that accused Niuniu’s parents of asking for special treatment, not following school’s rules, harassing the teacher and opposing other parents’ demand of enhancing after class training. After a few other clashes, the content of the petition became “evicting” Niuniu. Eventually, out of the 39 students in Niuniu’s class (including Niuniu), the parents of 37 students openly signed the letter, at which time Niuniu’s mother put the incident on the internet and ignited fierce disagreements.

At the first glance, it seems obvious who is at fault. Already in 2019, Guizhou province’s Department of Education has declared that “in the first and second years of elementary school, no paper homework can be assigned,” which means the teacher was violating the regulation in the first place. However, it should be noted that the elementary was the prestigious private Elementary School of Guiyang Attached to Beijing Normal University that is only open to the Jinhuayuan residential complex, where the housing prices are much higher than the nearby level. Niuniu’s mother is a researcher and Niuniu’s father owns a clinic. Presumably, other parents are also high income middle-class families, which is the most vulnerable social class to downward social mobility. They paid a lot for the school and are willing to push their children to their limits. They also knew that if they are not harsh to their kids, as Niuniu’s parents are, their kids will be surpassed by others who work harder. Therefore, they, as “cheaters” in the prisoner’s dilemma game, saw Niuniu’s parents, possibly the “cooperators” as the “cheaters” who wanted to drag down their children and families.

A Suggestion: Socialized Nurture

A lot can be done to lessen the competition and stress in China, or at least make the competition more fair and meaningful. However, not many solutions directly target the problematic structure of the prisoner’s dilemma. One potential solution is the socialized nurture popularized by media professional Ma Dugong, who has over a million followers on Bilibili. The term “socialized” in Chinese context is unlike the sociological “socialization” in English context. It primarily refers to having the state or other social institutions or groups to handle some obligations that were originally private to family, for example, “socialized caring-for-the-elderly” basically means “social pension.” Therefore, proponents of socialized nurture argue that the school should take more of the responsibility of raising kids because incompetent individual families are stressed out for their children’s education. In contrast, schools employ professionals and exhibit economies of scale. The compulsory education, for instance, is a form of socialized nurture compared to family-based nurture. The concept of socialized nurture is used to promote longer school days, better teachers, more comprehensive development at school, more group activities such as summer camps, and many other reforms that aim to raise able and all-round children who are accustomed to and robust in the new industrial society. Nonetheless, what lies at the heart of socialized nurture is for the legal structure to recognize the state as the principal guardian with custody that only lends partial custody to individual families when children are outside of schools. This is perhaps the most effective approach that can achieve the social optimality in a prisoner’s dilemma because the schools can directly regulate how much time of the students are spent on what. When the impartial regulator only gives students an hour a day on their homework and breaking the limit is illegal, players in the prisoner’s dilemma are more likely to trust each other and cooperate by only learning efficiently. Students with extraordinary interests and abilities in academic studying can go through a tracking system where they compete with other similar students on similar terms.

Of course, socialized nurture is a highly contested topics, but it deserves more discussions because the old agricultural family-based nurture structure shows more and more problems such as child abuse, population ageing, depression, social isolation, stressed out kids. Socialized nurture not only allows the whole society to examine the growth of individual children, but also recognizes each child as an independent citizen with rights rather than property of the family. A world with socialized nurture can rule out schools as total institutions, but the current law is impotent when Chinese parents put their kids into prison like schools.

Conclusion

In this essay, I reviewed existing literature on Chinese education, tested the prisoner’s dilemma type involution hypothesis, and suggested a road forward for Chinese education.

—-Atlas, 2021.12.3

Bibliography

Benjamin, D., Gunderson, M., Lemieux, T., Riddell, C. (2017). LABOUR MARKET ECONOMICS Eighth Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN-13: 978-1-25-903083-3

Chanye Xinxi Wang. (2019). 2019 Nian Zhongguo K12 Kewai Peixun Hangye Fazhan Xianzhuang Ji Shichang Guimo Yuce. [2019 Chinese K12 Out-of-School Tutoring Industry’s Current Development and Prediction of Market Size]. Retrieved from https://www.chyxx.com/industry/201906/744798.html

Chen, G. (2014). Minzu Diqu Yiwu Jiaoyu Zhili Neijuanhua Yanjiu. [On the Involution of Governance of Compulsory Education in Minority Areas]. Southwest University.

Chen, J. (2021). Jiaoyu Jianfu Zhengce Zhixing Shixiao De Boyi Fenxi. [A Game Theory Analysis to the Executive Failure of Education Burden Reduction Policy]. Theoretic Observation. (2021), 175.

ChinaNews (Zhong Xin She). (2020). Zhongguo Ertong Qingshaonian Jinshilv da 53.6%. [Chinese Children and Teenagers’ Myopia Rate is 53.6%]. Retrieved from https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gn/2020/06-05/9204202.shtml

Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Yiwu Jiaoyu Fa). (2006). Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/flfg/2006-06/30/content_323302.htm

Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Xianfa). (1982). Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2018-03/22/content_5276318.htm

Dello-Iacovo, B. (2009). Curriculum reform and ‘Quality Education’ in China: An overview. International Journal of Educational Development, 29. 241-249.

Du, J. (2020). Research on the change of the content of science mathematics test paper in the new curriculum standard of college entrance examination in recent ten years. Northwest Normal University.

Han, X., Cheng, Y. (2020). Consumption- and productivity-adjusted dependency ratio with household structure heterogeneity in China. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 17(100276). ISSN 2212-828X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2020.100276.

He, Z. (2012). Jiaoyu Xinhao De Jingji Fenxi. [An Economic Analysis of Educational Signaling]. People’s Publishing House.

Hou, J., Chen, Z. (2021). 2009 Nian he 2020 Nian Qingshaonian Xinli Jiankang ZhuangKuang de Nianji Yanbian. [The Change of Teenagers’ Mental Health Condition from 2019 to 2020]. Retrieved from https://www.pishu.com.cn/skwx_ps/databasedetail?SiteID=14&contentId=12369544&contentType=literature&subLibID=

Howlett, Z. M. (2021). Meritocracy and Its Discontents Anxiety and the National College Entrance Exam in China. ISBN13: 9781501754463

I Research (Airui Zixun). (2019). Zhongguo Qingshaonian Ertong Shuimian Jiankang Baipishu. [White Paper for Chinese Teenagers and Children’s Sleeping Health]. Retrieved from https://pg.jrj.com.cn/acc/Res/CN_RES/INDUS/2019/4/28/08512168-183e-4636-b069-0df3c728a511.pdf

Jingji Cankao Bao. (2017). Zhongguo Gaoji Jigong Quekou Da Qianwan. [Shortage of Chinese High-Skilled Technicians Reaches Twenty Million]. Retrieved from https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1663815

Jonathan, R. (1990). State Education Service or Prisoner’s Dilemma: The ‘Hidden Hand’ as Source of Education Policy. British Journal of Educational Studies, 38(2). 116-132. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3121193

Kang, O. (2004). Higher Education Reform in China Today. Policy Futures in Education, 2(1).

Liu, S. (2020). Neoliberalism, Globalization, and “Elite” Education in China: Becoming International. Politics of Education in Asia. Retrieved from https://www.routledge.com/Politics-of-Education-in-Asia/book-series/RPEA

Li X., Luo, K. (2021). The Underlying Logic and Institutional Governance of Super Secondary Schools: A Reflection and Review Based on the Hengshui Model. Fudan Education Forum, 19(5). DOI:10.13397/j.cnki.fef.2021.05.003

Loyalka, P., Liu, O.L., Li, G. et al. (2021). Skill levels and gains in university STEM education in China, India, Russia and the United States. Nat Hum Behav 5, 892–904. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01062-3

Ministry of Education. (2020). Jiaoyubu. [Ministry of Education]. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.cn/fbh/live/2020/52763/mtbd/202012/t20201211_504942.html

Peking University. (2021). Enrollment Information. Retrieved from https://www.gotopku.cn/programa/admitline/7/2021.html

Programme for International Student Assessment. (2015). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from https://pisadataexplorer.oecd.org/ide/idepisa/

Programme for International Student Assessment. (2018). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from https://pisadataexplorer.oecd.org/ide/idepisa/

Sohu. (2019). Yi Nian 275 Ren Kaoshang Qingbei, Yisuo Zhongxue Chengba Quansheng. [275 Students Got Admitted by Peking and Tsinghua University in One Year, One High School Dominated the Entire Province]. Retrieved from https://www.sohu.com/a/349466165_464033

Tang, X. [唐向宇]. (2018). School district housing (Xue Qu Fang) and the underlying problem of unequal distribution of educational resources : a study of Guangzhou city. University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR.

Wang, Y. (2019). Paradigm Shift of Education Governance in China Two Compulsory Education Legislation Episodes: 1986 vs 2006. Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-59513-8

Whyte, M. K. (2012). China’s Post-Socialist Inequality. Current History, 111 (746) China and East Asia, 229-234

Xiaoxiang Chenbao. (2020). Gongli Xuexiao Laoshi Zaiwai Sikai Fudaoban. [Public School Teachers Secretly Open Out-of-school Tutors]. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1682759163057005264&wfr=spider&for=pc

Xinhua Baoye Wang. (2021). Hebei Hengshui Zhongxue Xueba Yanjiang Shiping Yin Zhengyi. [Speech from Academic High Achiever from Hebei Hengshui High School Spurred Controversies]. Retrieved from http://news.xhby.net/index/202106/t20210602_7111260.shtml

Xinmin Wanbao. (2021). Shanghaishi Jiaowei Fuzeren Tan Shuangjian. [“Principle of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Talks about ‘Double Reduction’”]. [Video]. Bilibili. Retrieved from https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1mU4y1E7RA?p=1

Xiong, z. (2021). Zouchu Neijuanhua: Hanguo Jiaoyu Re de Leng Sikao. [Walking Out of Involution: A Cold Reflection on Korea’s Heated Education]. Gong Guan Shi Jie Li Lun Ban, 2021, 107-109

Xu, Z. (2020). Yingzi Jiaoyu Tisheng le Xueye Chengji Ma? [Did Shadow Education Increase Academic Scores?] Journal of Schooling Studies, 17(2).

Yi, Haiyue. (2021). Hengshui Zhongxue Biye De Wo, Caifang Le Sanwei Xiaozhang. Yilin.

Zhao, X., Selman, R. L., Haste, H. (2015). Academic stress in Chinese schools and a proposed preventive intervention program. Cogent Education, 2:1(1000477), DOI: 10.1080/2331186X.2014.1000477